Did tax increases deepen and extend the Great Depression?

That is one topic explored in a new book by Art Laffer, Brian Domitrovic, and Jeanne Cairns Sinquefield, Taxes Have Consequences: An Income Tax History of the United States. The authors include a discussion of federal, state, and local tax increases during the 1930s.

Many economists would point to monetary policy mistakes for causing the initial slide into the Great Depression. The nation’s money supply fell nearly 30 percent between 1930 and 1933.

But Laffer and coauthors argue that the “chief cause of the Great Depression was taxation.” That is a bold claim because policymakers made many mistakes during the 1930s. Aside from adverse monetary and tax policies, the government undermined the economy with regulatory interventions, labor union laws, and a general antagonism toward businesses and high earners. George Selgin discusses the era’s economic policies here.

Let’s explore the major tax increases of the 1930s, based on the Laffer book, an analysis by Alan Reynolds, and numerous other sources. Herbert Hoover signed the first two laws listed here and Franklin Roosevelt the others.

- Smoot‐Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. Signed in June, the act raised import tariffs on thousands of goods. Two‐thirds of the tariffs were specific charges per unit, so the real burden rose as prices fell during the early 1930s. In response, foreign nations retaliated against U.S. trade. The stock market dropped coincident with the congressional debate and passage of the law.

- Revenue Act of 1932. The law was signed in June but retroactive to January. It increased all individual income tax rates with the top rate rising from 25 percent to 63 percent. The act broadened the income tax base, raised the corporate tax rate from 12 percent to 13.75 percent, and increased the top estate tax rate from 20 percent to 45 percent. The act also imposed a slew of large excise tax increases on items such as cars, tires, radios, and electricity. As a result, excise taxes raised more federal revenue than income taxes the rest of the decade.

- Gold Confiscation. Roosevelt issued an executive order in April 1933 requiring all Americans to hand over to the government all their gold worth more than $100 for payment at a set price per ounce. After the government grabbed the gold, it set a higher price in 1934 thus devaluing the dollars that people had received. Laffer and coauthors say the “gold confiscation was a wealth tax, pure and simple.”

- Agricultural Adjustment Act. This May 1933 law imposed processing taxes on agricultural products that raised an enormous $526 million a year by 1935, or more than 10 percent of federal revenues. Wheat and hogs were big tax revenue producers. The law was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1936.

- National Industrial Recovery Act. This June 1933 law imposed capital stock and excess profits taxes on corporations and a short‐lived five percent tax on dividends.

- Alcohol. Prohibition ended in 1933 and federal and state governments began collecting large revenues from beer, wine, and liquor. The federal liquor tax rate was almost tripled between 1933 and 1940, and state liquor tax rates were also increased. Probably because of the high taxes, bootlegging was still a major problem at the end of the decade.

- Revenue Act of 1934. Passed in May, this law broadened the income tax base and aimed to reduce tax avoidance (exacerbated by now‐higher tax rates) by increasing taxes on personal holding companies. The act also raised the top estate tax rate from 45 percent to 60 percent.

- Revenue Act of 1935. Passed in August, this law hiked top‐end individual income tax rates, with the highest rate rising from 63 percent to 79 percent. The act also increased taxes on corporations a number of ways, including raising the top corporate tax rate from 13.75 percent to 15 percent.

- Social Security Act of 1935. This law imposed one percent payroll taxes on both employers and employees effective in 1937.

- Revenue Act of 1936. Passed in June, this law imposed a surtax of up to 27 percent on undistributed corporate profits on top of the normal corporate income tax. The idea was to hit corporations that had been retaining earnings in response to the high tax rates on individuals.

- Revenue Act of 1937. This law broadened the income tax base and imposed new rules to reduce tax avoidance in response to Treasury concerns that the 1936 tax hike were not raising as much revenue as expected.

- Revenue Act of 1938. This law—combined with follow‐on legislation in 1939—repealed the undistributed corporate profits tax after widespread recognition of the damage it was causing to business investment. FDR opposed repeal and allowed the act to become law without his signature.

FDR had a misguided zeal to penalize high earners and corporations, and Hoover had a misguided zeal to balance the government’s budget with his 1932 tax hike. Hoover’s signing statement here illustrates his government‐centric view of fiscal policy.

State and Local Tax Increases

State and local governments jacked up taxes during the 1930s.

- Property taxes hit hard in the early 1930s because assessments often remained high even as incomes were falling. Nationwide, property tax revenues increased from 4.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1929 to 7.4 percent by 1932.

- General sales taxes were adopted by 23 states during the 1930s.

- Individual income taxes were adopted by 17 states during the 1930s.

- Corporate income taxes were adopted by 15 states during the 1930s.

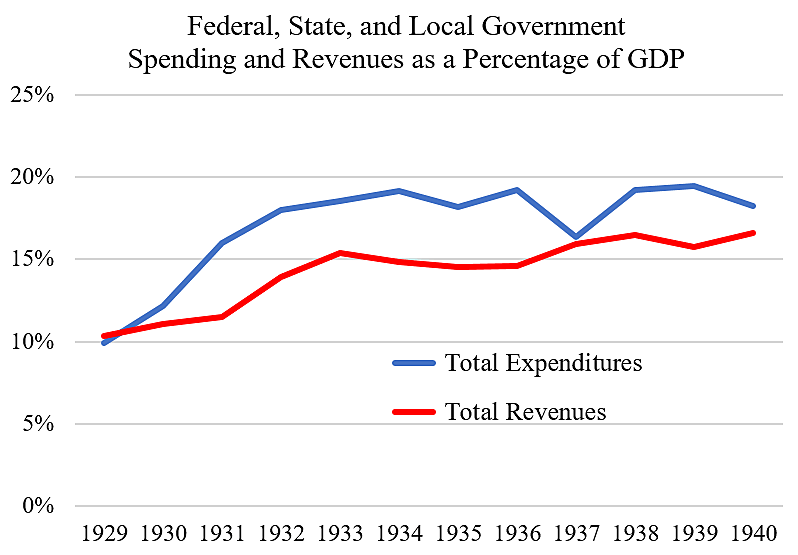

The chart below shows total federal, state, local revenues and spending as a percentage of GDP, based on national income data. Total tax revenues dropped between 1929 and 1932 but GDP fell much further, which resulted in taxes rising substantially as a share of GDP. Early in the 1930s, the largest revenue increases as a share of GDP were local property taxes and federal excise and customs taxes. Later in the decade, those revenue sources faded and federal income and payroll taxes grew.

Taxpayer Responses

Tax revenue data only partly captures the harm imposed on the private sector by tax increases. Taxpayers respond to tax hikes by changing their behavior. The larger the changes the more economic damage is done, which is referred to as deadweight losses. Large taxpayer responses also reduce government revenues. Thus if the government jacks up income tax rates on high earners, and they respond by substantially reducing productive activities and increasing tax avoidance, it would create major economic damage but raise little revenue.

Alan Reynolds finds that high earners responded strongly to the income tax increases of the 1930s, which is supportive of the analysis in the Laffer book. Reynolds shows that the reported incomes of high earners got slugged in the early 1930s and remained low the rest of the decade. This suggests major economic damage.

At the local level, taxpayers responded strongly to rising property taxes. Tax revolts spread across the nation in the early 1930s because millions of people were suffering and could not afford to pay their property taxes. Citing a history by David Beito, Laffer and coauthors report that for cities over 50,000 in population, the median property tax delinquency rate rose from 10 percent in 1930 to 26 percent by 1933. In Chicago, about half of homeowners were refusing to pay their property taxes by 1932.

The large undistributed profits tax imposed in 1936 was widely criticized by business leaders for undermining investment. In response to the outcry, the tax was repealed in the revenue laws of 1938 and 1939. More generally, U.S. real private investment plunged in the early 1930s and only fully rebounded to surpass the 1929 level in 1940. (1.1.6)

Rising federal and state alcohol taxes during the 1930s appears to have caused a large tax‐evasion response. A 1941 article noted, “The Alcohol Tax Unit of the Bureau of Internal Revenue had 4,184 employees on December 31, 1940, of whom 1,293 were investigators and special investigators. These men, successors to the prohibition agents of fifteen years ago, are kept fully occupied in the business of trying to prevent bootlegging and the operation of illegal stills. The extent of liquor law violations is indicated by the fact that convictions totaling 4,941 persons, or 46.5 per cent of all federal prisoners committed to penitentiaries in the fiscal year 1940, were attributed to the work of the Alcohol Tax Unit.”

Despite these taxpayer responses to higher tax rates, the chart shows that governments did manage to squeeze substantially more money out of the public during the 1930s. Tax revenues as a percentage of GDP rose from 10.3 percent in 1929, to 15.4 percent in 1933, and then to 16.6 percent in 1940. Meanwhile, government spending soared from 9.9 percent of GDP in 1929 to 18.0 percent in 1932, and then remained near the higher level the rest of the decade.

Notes: I estimated total government expenditures from BEA’s Table 3.1 as current expenditures plus gross investment less consumption of fixed capital. Taxes, including Social Security payroll taxes, were about 94 percent of BEA’s total government revenues or “receipts” during the 1930s. A good survey of policy mistakes during the 1930s is Jim Powell’s FDR’s Folly: How Roosevelt and His New Deal Prolonged the Great Depression. A source for the tax history of the 1930s is W. Elliot Brownlee, Federal Taxation in America: A Short History.