The IRS has released a new estimate of the “tax gap,” which is the amount of federal taxes owed but not paid. Basically, this is the amount of cheating on federal taxes. The IRS report contains good news. Tax cheating is not a growing problem relative to the size of the economy, despite all the political rhetoric to the contrary.

The IRS found that the annual gross tax gap for 2014–2016 was $496 billion. After late payments and enforcement actions, the net tax gap was $428 billion. Of the net total, $306 billion stemmed from individual income taxes, $34 billion from corporate income taxes, $87 billion from payroll taxes, and $2 billion from estate taxes.

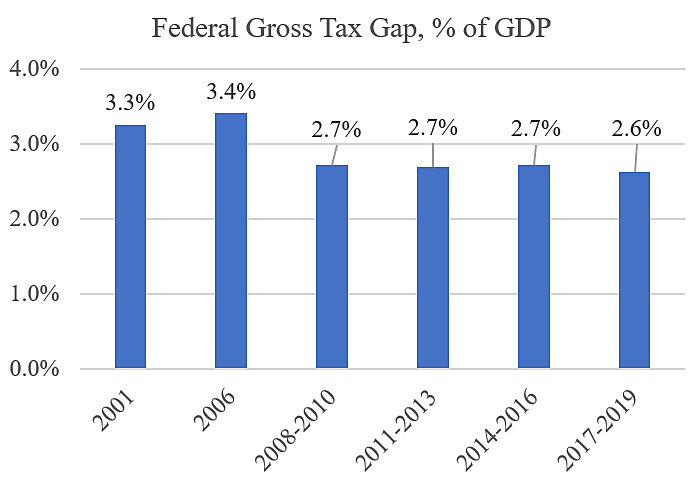

The new report includes gross tax gap estimates for prior years, which were $345 billion in 2001, $472 billion in 2006, $394 billion in 2008–2010, and $438 billion in 2011–2013. The IRS also projected the gap for 2017–2019 to be $540 billion. The dollar value of the tax gap has increased, but the gap has not increased when compared to the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), as shown in the chart. (I’ve used the GDP of the middle year for the multiyear estimates).

The flip side of the gross tax gap is the “voluntary compliance rate,” which is the tax paid on time divided by the estimated full amount owed. The IRS report shows that the voluntary compliance rate rose from 83.7 percent in 2011–2013 to 85.0 percent in 2014–2016. The IRS projects the rate to be 85.1 percent in 2017–2019.

To me, the IRS report suggests that the tax gap is not a major problem. The gap is stable relative to the size of the economy, and our tax gap is smaller than the average tax gap in Europe, as I discuss here.

Given our stable and relatively small tax gap, President Biden’s expensive effort to boost IRS enforcement is misguided. There are civil liberties trade‐offs to consider when trying to close the tax gap with enforcement, as I discuss here. The optimal tax gap is not zero because that would require a more powerful government and impose higher compliance costs on taxpayers. And even with more power, the IRS would not achieve fully accurate tax payments because the agency itself makes frequent errors.

That said, there is a win‐win approach to reducing the tax gap. Simplifying the tax code and cutting tax rates would reduce the ability and incentive for taxpayers to cheat. It would also cut compliance costs and increase civil liberties. Tax simplification should be on the agenda of the new Congress in 2023.