In 1990, a Department of Transportation researcher named Don Pickrell looked at ten rail transit projects completed in the 1980s and found that their construction costs averaged 62 percent more than originally projected, their operating costs were 130 percent more, and their ridership was 47 percent less than projected. He observed that such huge cost underestimates and ridership overestimates biased any analysis in favor of capital‐intensive projects like rail construction.

For his efforts, Pickrell was transferred to another part of the DOT and told never to write about transit again. But cost overruns continued and starting in 2003 the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) was forced to write a series of reports comparing the projected with actual costs and ridership for more recent rail projects. Most of these reports found similar cost overruns and ridership underestimates. (You can find a list all of these projects and their cost overruns and ridership underestimates in my five‐page policy brief.)

However, reports on projects completed in the 2010s found that cost overruns were much smaller and in many cases there were no overruns. A close scrutiny of these reports, however, reveals that the FTA has changed the goal posts. Where Pickrell and earlier FTA reports compared cost projections at the time transit agencies decided to build a project, the more recent FTA reports compared the projections made at the time the FTA decided to start funding the project, which is usually much later.

For example, a proposed rail line in Denver was sold to voters in 2004 with the promise that it would cost under $1.2 billion. By the time the proposal reached the FTA, costs had doubled to $2.4 billon. The transit agency made some cuts (such as single‐tracking some sections that would normally be double tracked, creating operational problems) and managed to complete the project for $2.0 billion. Under the FTA’s old methodology, that would be a 67 percent cost overrun, but under the new methodology, it would appear to be a cost underrun.

One project that disproves any notion that transit agency estimates are getting better is the Honolulu rail line. Projected to cost under $5 billion when the city approved it, it is now expected to cost more than $12 billion, making it the tsunami of cost overruns. It is also expected to be completed about 11 years late. Plus, the transit agency building it has reduced its ridership projections by 18 percent, and considering changes people are making since the pandemic, that is still optimistic. Honolulu should cancel the project, but like nearly all transit agencies it will continue to throw good money after bad.

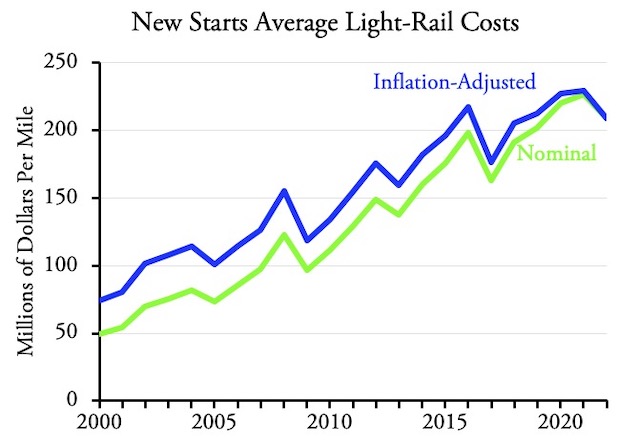

Light‐rail projects included in the FTA’s annual transit capital grants (New Starts) reports have tripled in inflation‐adjusted cost in the last two decades.

Light‐rail projects included in the FTA’s annual transit capital grants (New Starts) reports have tripled in inflation‐adjusted cost in the last two decades.

Regardless of overruns, costs have risen dramatically. The FTA publishes an annual report listing all of the projects it is funding or considering for funding. The light‐rail lines included in the report for 2000 cost an average of $49 million per mile (which is about $74 million per mile in today’s money). The light‐rail lines in the FTA’s 2021 report cost an average of $229 million per mile, a near‐tripling since 2000. This increase is largely because transit agencies have figured out that the federal government will fund projects no matter how expensive or cost‐effective they are.

Outside of New York City, rail transit is functionally obsolete, and construction costs in New York are so high that building more there isn’t worth it either. In general, buses can move more people per hour at faster speeds to more destinations for a far lower cost than rail transit.

But that doesn’t mean transit agencies should start spending a lot of money on buses, as suggested by a recent Washington Post article describing cities that are supposedly “supercharging their bus routes.” What the article means is that some cities are converting lanes once open to automobiles into dedicated bus lanes and/or giving buses priority over cars at traffic lights. This is just one more way for transit agencies to spend taxpayer dollars staking a claim that transit riders are somehow morally superior to auto drivers and therefore deserve privileges denied to auto users.

The real problem with transit is not a shortage of funds; it is that transit agencies have too much money from federal, state, and local governments, and so they cater to the whims of politicians rather than to their customer needs. Most transit systems are still operating on a nineteenth‐century business model and they expect their users to conform to their model rather than change their model to meet modern transportation needs.

Especially during and after the pandemic, when transit ridership is down by more than 55 percent and not likely to ever fully recover, it makes no sense to throw more money at it. Instead, we should end transit subsidies and let the transit agencies learn to serve their riders rather than the latest political fad.

Departments:

Themes: