Dear Capitolisters,

Last Wednesday, I needed to go to New York for the day to film an interview for a forthcoming video on the Jones Act (stay tuned). The plan was something I’d done with little trouble, exhaustion notwithstanding, over the years: Arrive early morning, do the hit, and return home late that night. Last Wednesday, however, was not your typical travel day—thanks to an early‐morning meltdown of the U.S. air traffic control (ATC) system.

Unfortunately for me and many other U.S. travelers, airlines didn’t simply proceed as planned once the ATC system was rebooted. In my case, in fact, we boarded, taxied out to the runway, and—literally seconds before taking off—stopped everything and just sat on the tarmac for an hour. Then, we went back to the gate and waited there. Then we boarded again, waited on the tarmac again, and returned to the gate again. Then I changed flights, finally arriving in Manhattan seven hours later than planned. Then my return flight was delayed another two hours because of continued backlogs. All in all, I spent more than nine hours in airports and less than four hours in New York. And nobody knew anything the entire time. Fun stuff.

My miserable day, however, did have a small silver lining: It provides us with a perfect opportunity to discuss America’s antiquated air traffic control system and the urgent need and obvious way to reform it.

So What Exactly Happened?

It’s still not entirely clear why the U.S. ATC system needed a total reboot in the first place, but the preliminary word from the Federal Aviation Administration was that “two people working for a contractor introduced errors into the core data used on the system known as Notice to Air Missions [NOTAM],” which are “advisories to pilots on safety‐critical conditions at airports and other areas aircraft might traverse.” That caused a system‐wide problem because the ATC’s backup system (oddly) relied on the same buggy file:

When the system began having problems Tuesday night, technicians switched to a backup. But because the backup was attempting to access the same damaged data, it also didn’t work….

A complete shutdown was required to restore the system, leading the FAA to halt all flight departures for roughly 90 minutes Wednesday morning.

As already noted, U.S. domestic flights were a mess nationwide for the rest of the day. (Grumble.)

According to the same report, we don’t yet know if the data file was corrupted “accidentally or intentionally.” In the meantime, “the agency is attempting to create new protections to prevent such a failure in the future,” but—and here’s a key tell—“portions of the Notam computer system are as old as 30 years.”

Our Long History of ATC Problems

That the NOTAM system is so old, and that the system collapsed so fully, will come as no surprise to anyone versed in U.S. transportation policy. The federal government, in fact, has been looking to modernize the antiquated U.S. ATC system since the early 2000s, when Congress first began exploring the issue and in 2003 enacted a plan to drag U.S. air traffic into the 21st century (or, as we’ll discuss below, more like the late 20th). The result of these efforts was the FAA’s multibillion dollar “Next Generation Air Transportation System” (NextGen) project, which the agency began implementing in earnest in the mid‐2000s with an original completion date of 2025.

That deadline will be missed.

As multiple independent and government reports have documented, the FAA’s modernization efforts have been plagued with problems—overhyped benefits, cost overruns, long delays, epic mismanagement—and are far from complete today. A 2017 Government Accountability Office report found that NextGen had consistently remained behind schedule: It was supposed to have 10 of 30 “Metroplex” projects (the busiest airports) completed by 2016, but had completed only four as of March 2017. According to a 2021 inspector general report, the FAA first projected NexGen would produce $213 billion in benefits (more and safer flights, fewer delays, etc.), but this projection had been cut by more than half ($100 billion) a decade later. Actual results were even more damning: Between 2010 and 2018 (i.e., more than a decade after the FAA started the project), NextGen had realized benefits of only $6 billion at total cost of $9 billion, and projects were taking almost twice as long (four or five years) to complete as first planned (two to three years). Even this estimate might be too kind: NextGen “benefits actually achieved to date have been minimal and difficult to measure,” according to the inspector general, who anticipated that actual benefits will end up being even lower than the FAA’s already lowered estimates.

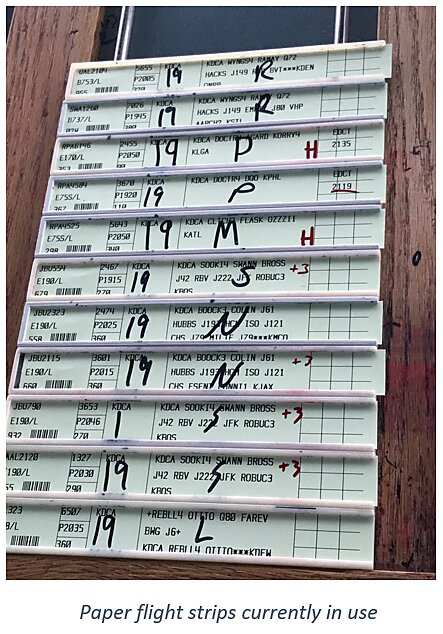

As a result of these implementation problems, much of the U.S. ATC system remains ridiculously antiquated, despite receiving tens of billions of taxpayer dollars to fix this very thing. For example, many U.S. airports still use paper flight strips to keep track of flights—a “technology” that dates back to the mid‐20th century (click the link for a laugh):

As Reason Foundation’s Marc Scribner noted in November, “Electronic flight strips replaced paper strips years ago in Canada, the United Kingdom, and most of Europe, but FAA doesn’t anticipate finishing its planned 89‐site deployment of TFDM until 2031.” According to the agency’s website, in fact, most of the biggest U.S. airports in the country—JFK, DFW, O’Hare, LAX, Hartsfield (Atlanta), etc.—and many others are still using paper flight strips and won’t upgrade to electronic ones for several more years. The ATC’s antiquity extends to the NOTAM system too, which the FAA itself acknowledges: In its latest Fiscal Year 2023 budget submission, for example, the agency earmarked $29.4 million to “eliminate the failing vintage hardware that currently supports [NOTAMs] in the national airspace system.”

“Vintage”! Yikes.

Why are we still even talking about paper strips and “vintage” systems in 2023 when NextGen has been supposedly in place for more than 15 years now and many other countries modernized years ago? According to numerous experts, one problem is simply the nature of the FAA’s and ATC’s funding:

The [NOTAM] system is “immeasurably complex”, [former FAA official David] Soucie said, receiving feeds of information from hundreds of sources, ranging from airports to the US Department of Defense. Updating and improving the regulator’s information technology systems is a process that takes years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars, yet the political appointees who run the FAA “aren’t in place long enough to see these things through and make sure there’s funding in Congress.”

Other reports note that U.S. funding for airports and ATC systems can also fall victim to good ol’ pork barrel politics, with members of Congress protecting FAA jobs and facilities in their districts and directing taxpayer dollars to pet projects instead of systemic reforms.

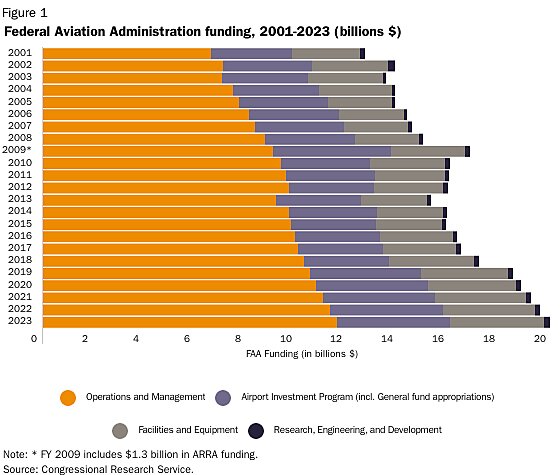

But these same experts are quick to add that there is far more at issue here than simple appropriations and appointee issues, with which every U.S. government agency deals. For starters, the FAA is at essentially zero risk of a major funding cut and instead has seen strong inflow of cash regardless of who’s running the executive and legislative branches:

According to the most recent Congressional Research Service report, about 90 percent of FAA funding (roughly $15 billion) comes from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund, which is comprised of taxes and fees on passengers and airlines and has a healthy cash balance of roughly $17 billion. Additional funding comes from the general fund, and the 2021 infrastructure law will send the FAA another $25 billion in general fund appropriations through 2026.

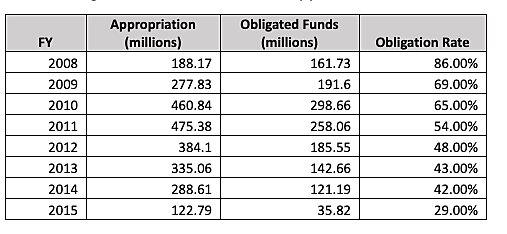

The FAA isn’t just well‐funded; it’s not spending the funds it has. In fact, a 2018 inspector general report found that the FAA routinely left on the table large amounts appropriated for NextGen developmental (i.e., pre‐implementation stage) projects. Available annual funds often exceeded $500 million, but the FAA never obligated more than $300 million in any year between 2008 and 2015:

Instead, the FAA and ATC’s problems are systemic. As the Washington Post reported following the 2018 IG report’s release, the FAA “mishandled” the funds provided because the agency lacks “a clearly established framework for managing the overall oversight of NextGen” and “has lacked effective management controls” in awarding contracts. Sometimes, the FAA “spent money on low‐priority projects” and directed hundreds of millions of dollars to projects that hadn’t yet been approved. The Post adds that this “was the fourth inspector general’s critique” of the NextGen program, all of them bad, and then we got a fifth in 2021.

These problems have been widely recognized for decades—and not just by libertarians like me. In 2005, for example, the GAO reported that, “For more than two decades [i.e., since the 1980s!], ATC system acquisitions under the National Airspace System modernization program have experienced significant cost growth, schedule delays, and performance problems.” Then in 2008, the Brookings Institution’s Dorothy Robyn explained that “the FAA is poorly suited to run what amounts to a capital‐intensive, high‐tech service business,” and that it suffers from a conflict of interest as both the ATC operator and regulator. She thus cautioned that, without major reforms, “the severe and systemic problems that have plagued past FAA modernization efforts are almost certain to persist.” (Nailed it!) A 2009 video from Reason documented that ATC reform has attracted attention since the Clinton administration, quoting both Bob Stone (Al Gore’s right‐hand man for the administration’s “Reinventing Government” initiative) and ATC expert Robert Poole (from the Reason Foundation and the Hudson Institute) on the need for reform.

My Cato colleague Chris Edwards summarized Poole’s 2015 report on the FAA’s systemic problems:

Poole found that the agency is risk averse, slow to make decisions, and mismanages procurement. It loses skilled people to private industry because of a lack of pay flexibility and frustration with the government work environment. Poole found that the FAA “is slow to embrace promising innovations,” and is “particularly resistant to high‐potential innovations that would disrupt its own institutional status quo.”

So we get paper strips, vintage equipment, nonsensical backup plans, and a nationwide flight debacle because of a single bad data file.

A Better Alternative

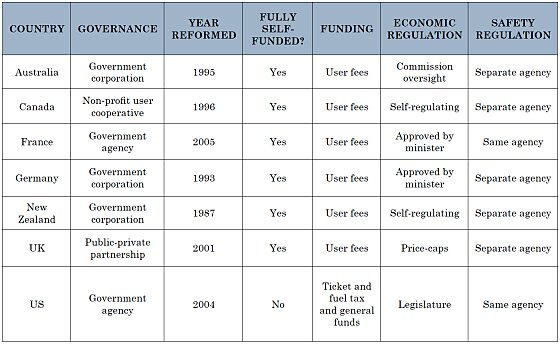

Fortunately, there’s a better way to manage national ATC systems—privatization. As Edwards and others have noted (see, for example, this from National Review’s Dominic Pino), there is no good reason for the U.S. government to run the ATC system, and decoupling it from the FAA would improve ATC operations and avoid its longstanding problems. As Poole noted in 2017, dozens of other countries have taken this route (pun!):

Over the past 30 years, more than 60 countries have separated their air traffic control systems from their transportation agencies, converting air traffic organizations to self‐funded companies, regulated for safety. The largest of these ATC providers, like Nav Canada and the United Kingdom’s NATS, have investment‐grade bond ratings that help modernization efforts. Nav Canada’s air traffic control unit costs are 26 percent less than FAA‘s, despite FAA supposedly having economies of scale due to its larger size. These companies have consolidated numerous control centers into a smaller number of high‐tech replacements — without political interference. Nav Canada and others are at least a decade ahead of FAA on upgrades of technology and procedures. And a growing body of studies shows that ATC systems perform better following “corporatization.”

The Eno Center for Transportation provides a handy table of some of these countries and their reforms, which vary in design but uniformly depoliticize funding via user fees instead of taxes and legislative appropriations:

As Poole, Edwards, Pino, and other analysts have noted, the Nav Canada system has been particularly successful, improving not only efficiency, innovation, and transparency, but also safety. The airline industry agrees:

Nav Canada has won three International Air Transport Association (IATA) Eagle Awards as the world’s best ATC provider. The IATA has said that Nav Canada is a “global leader in delivering top‐class performance” and that its “strong track record of working closely with its customers to improve performance through regular and meaningful consultations, combined with technical and operational investments supported by extensive cost‐benefit analysis, place it at the forefront of the industry’s air navigation service providers.”

Such world‐class performance surely could’ve come in handy during last week’s NOTAM debacle, which might have been avoided—or, at least, significantly mitigated—with better technology, systems, and personnel. Indeed, Nav Canada coincidentally had its own NOTAM outage last Wednesday—both the U.S. and Canada vehemently deny it was a coordinated cyberattack, by the way—but Canada’s ATC system didn’t have a single domestic flight delay:

Maybe that too is a coincidence (owing to a different type of NOTAM outage, for example), but the FAA’s track record gives us a very strong reason to suspect otherwise.

So, if everyone recognizes the need for systemic reform, and if many countries have implemented smart reforms to decouple ATC systems from their governments, then why doesn’t it happen here? Well, as the Eno Center’s Jeff Davis reported back when the last reform push in 2018 failed, it came down to intense opposition from four important groups:

- Private aircraft owners and operators, who use all or most (depending on the plane) of the same ATC resources as the big passenger airliners but pay a fraction of the cost under the current system

- Federal employee unions—a “key constituency of the Democratic Party”—who saw efficiency‐enhancing reforms as a threat to their numbers and leverage;

- Congressional appropriators, including most Republicans, who gained political power and campaign donations from controlling ATC‐related purse strings; and

- Many senior and midlevel FAA officials, who saw that reform would cause the agency to lose “about three‐fourths of its employees and its annual budget.”

In other words, it’s your standard political problem (and American Sclerosis once again).

Summing It All Up

The failure of a U.S. government agency to quickly improve a critical part of the U.S. economy, despite ample funding and precedent, is admittedly a dog‐bites‐man story—especially for this newsletter. But it’s always good to identify another example of the problem (for several others, see Colin Grabow’s transportation policy chapter in my new book) and to contrast it with private sector actors that usually face far more, and far more immediate, pressure to fix their mistakes and improve the customer experience. Indeed, just a few weeks before the ATC debacle, Southwest Airlines suffered a major bout of flight cancellations, reportedly because of outdated technology and other things. The response from investors was swift: The company’s stock dropped around 10 percent in the days surrounding Christmas, and several shareholders have since filed a lawsuit. Customers, meanwhile, promised never to fly the airline again, and experts warned of severe reputational damage for time‐sensitive business travelers.

Within a matter of days, however, Southwest responded: It sent stranded travelers 25,000 frequent flier miles and used digital payment apps (Venmo, Paypal, etc.) to quickly issue them cash refunds and reimbursements; it launched a major airfare sale to try to maintain its customer base; it hired an independent consulting firm to investigate the collapse and hired GE Digital to implement technology upgrades. The company also publicly estimated that the fiasco will cost it about $825 million and drag down its fourth quarter financial results. Less than a month later, the company’s stock had recouped its Christmastime losses—a small (and admittedly imperfect) sign that investors were happy with the company’s efforts.

Now, this of course doesn’t mean that Southwest will do everything it says it’s going to do, or that its changes will avoid another catastrophe. But the company’s speed, responsiveness, and transparency stand in stark contrast to the FAA’s and other U.S. officials’ slow, opaque hot dog man routine. And if I were a betting man, I’d wager good money that last week’s ATC outage will result in a congressional hearing or two, a government report on the mess (maybe, eventually), and a grand total of zero actual, systemic reforms to NextGen or any other part of the U.S. ATC system. (And my Venmo account is sure as heck not gonna be seeing any reimbursement for the entire day I lost in the airport.)

All of this is worth remembering the next time you hear someone again proposing we nationalize a strategic industry (no, really, people are still doing that). Stuff happens, and humans make mistakes. But in the market, private actors respond quickly because persistently bad behavior gets punished.

In the U.S. government, it gets you a raise.

Departments:

Themes: