The federal government employs 2.1 million civilian workers in hundreds of agencies at offices across the nation.1 The federal workforce imposes a substantial burden on America’s taxpayers. In 2019 wages and benefits for executive branch civilian workers cost $291 billion.2

Since the 1990s, federal workers have enjoyed faster compensation growth than private-sector workers. In 2018 federal workers earned 80 percent more, on average, than private-sector workers.3 And federal workers earned 47 percent more, on average, than state and local government workers.4 The federal government has become an elite island of secure and high-paid employment separated from the ocean of average Americans competing in the economy.

Spurred by large budget deficits, policymakers imposed a partial freeze on federal wages from 2011 to 2013, which saved billions of dollars. However, further savings are needed. Policymakers should turn their attention to the overly generous benefit packages received by federal workers. They should also cut the size of the federal workforce by terminating low-value programs and reducing layers of management.

Trends in Federal and Private Pay

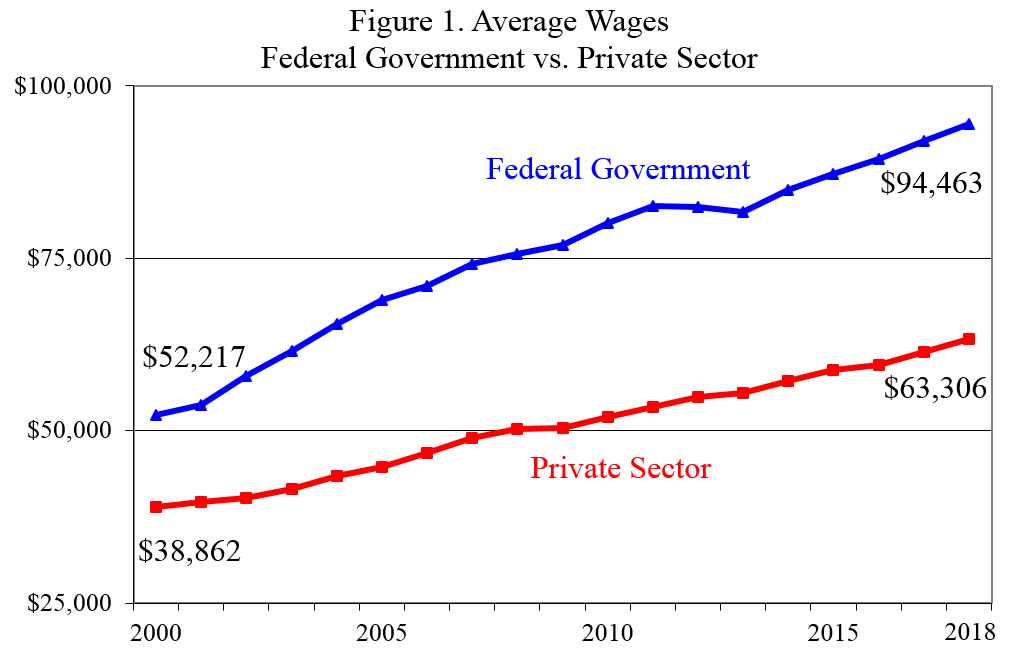

In 2018 federal civilian workers had an average wage of $94,463, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).5 By comparison, the average wage for the nation’s 118 million private-sector workers was $63,306. Figure 1 shows that average federal wages grew rapidly for a decade, then slowed during the partial pay freeze, and then have risen again in recent years.

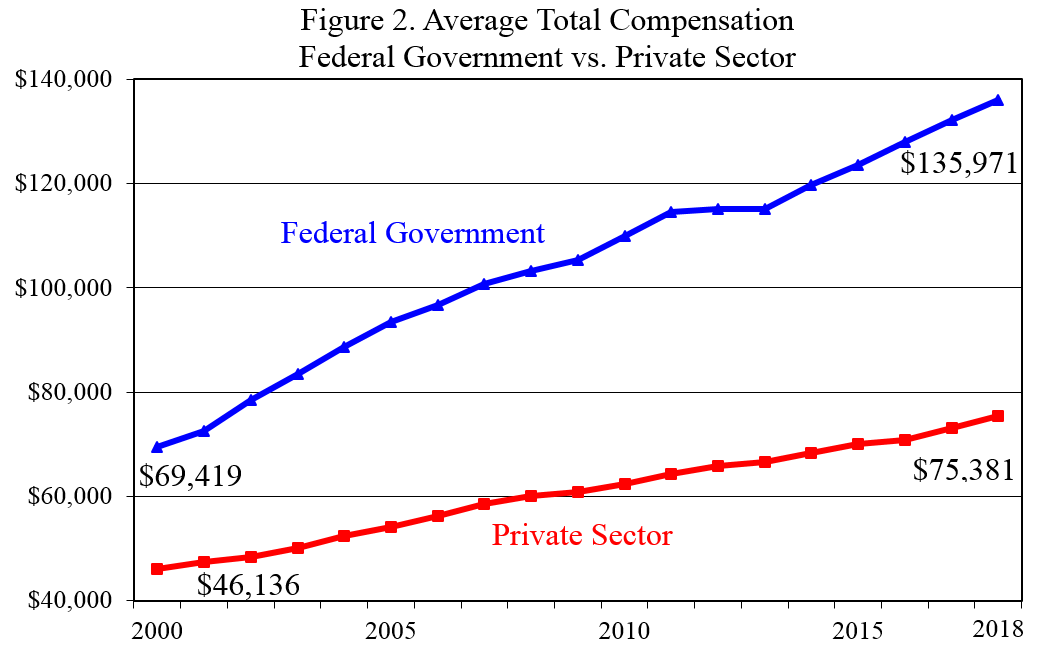

When benefits such as health care and pensions are included, the federal compensation advantage over private workers is even larger, according to the BEA data. In 2018 total federal compensation averaged $135,971 or 80 percent more than the private-sector average of $75,381, as shown in Figure 2.

The BEA data can be broken down by industry. Among 21 major sectors that span the U.S. economy, the federal government has the third highest paid workers after only utilities and management of companies.6 Federal compensation is higher, on average, than compensation in the information industry, finance and insurance, and professional and scientific industries.

Rising federal compensation stems from legislated increases in general pay, increases in locality pay, expansions in benefits, and growth in the number of high-paid jobs as bureaucracies become more top-heavy. Compensation growth is also fueled by routine adjustments that move federal workers into higher salary brackets regardless of performance, and by federal jobs that are redefined upward into higher pay ranges.

Politics also plays an important role. Federal workers are a powerful special-interest group, and they are effective lobbyists. Federal unions actively oppose legislators who support restraining worker pay. At a 2015 conference, for example, the head of a major federal union aggressively denounced lawmakers who stood in their way as “fools,” and said that the union would “open up the biggest can of whoop ass on anyone” who opposed its demands on pay and other issues.7 Members of Congress who have large numbers of federal workers in their districts often lead the efforts to expand pay and benefits.

Some people argue that the government has a unique high-end workforce that deserves to be paid handsomely. But the federal workforce has always had a heavy contingent of skilled professionals, such as lawyers. So that factor does not seem to explain why federal compensation has grown faster than private-sector compensation in recent decades. In 1990 average federal compensation was 39 percent higher than average private compensation.8 By 2000 the federal pay advantage had jumped to 50 percent, and by 2018 it was 80 percent.

In the past, there was a view that it was a privilege for citizens to serve the public in a federal agency, and that federal pay should be fairly modest. Unfortunately, that sort of thinking has gone out the window as the federal compensation advantage has continued to increase.

Federal Wages

Despite the escalation of federal compensation over the years, labor unions still complain that federal workers are underpaid. Looking only at wages, they say that federal workers suffer from a large “pay gap” compared to private-sector workers. They point to an annual memo released by the Federal Salary Council, which in 2015 indicated that federal workers were underpaid by 35 percent.9 But these results differ from other studies, and they are based on complex and nontransparent calculations that some experts argue are “deeply flawed.”10

Other studies based on comparisons between similar federal and private workers find either no wage gap or a federal wage advantage. A 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study found that, for comparable workers, federal wages were similar to private wages overall, with a three percent advantage for federal workers.11 However, the CBO also found large differences based on education levels. Among less-educated workers, the federal government pays better, but among highly educated workers, the private sector pays better.

Statistical studies by thinktanks have found a wage advantage for federal workers. A 2010 study by the Heritage Foundation found that federal pay was 22 percent higher, on average, than private-sector pay for comparable workers.12 A 2011 American Enterprise Institute (AEI) study found that federal pay was 14 percent higher, on average, than private-sector pay for comparable workers.13 As with the CBO study, these two studies found wage differences that varied by the level of the worker—less educated workers tend to do better in the federal government, while highly educated workers might do better in the private sector.

A 2010 USA Today analysis of more than 200 occupations found that federal workers typically have wages 20 percent higher than private sector workers.14 The analysis found that “federal employees earn higher average salaries than private sector workers in more than 8 out of 10 occupations.”15

Employee Benefits

The Bureau of Economic Analysis provides data on the average value of federal and private sector benefit packages.16 In 2018 federal workers enjoyed average annual benefits of $41,508, which compared to average benefits in the private sector of just $12,075. That large difference stems from more federal workers receiving certain types of benefits than private workers, and from particular federal benefits being more generous than those provided in the private sector.

Studies comparing federal and private benefits for similar workers have found a large federal advantage. The 2017 CBO study found that cost of employee benefits was 47 percent higher for federal civilian employees than for similar private-sector employees.17 CBO found that “The most important factor contributing to differences between the two sectors in the costs of benefits is the defined benefit pension plan that is available to most federal employees.”18 The AEI and Heritage studies also found large federal advantages with respect to worker benefits.

Federal workers receive health insurance, retirement health benefits, a pension plan with inflation protection, and a retirement savings plan with a government match. They typically receive generous holiday and vacation schedules, flexible work hours, training options, incentive awards, and generous disability benefits.

Lily Garcia, a human resources specialist who contributes to the Washington Post, noted: “The primary advantages of working for the federal government are generous benefits, solid pay, and relative job security, a combination that is challenging to find in the private sector, even in the best of times.”19 Garcia summarized the federal benefits package:20

- “Health Care: The Federal Employee Health Benefits Program offers the widest selection of health care plans of any U.S. employer. Federal employees also have access to vision and dental plans, life insurance, flexible spending accounts, and long-term care plans.”

- “Paid Time Off: Federal employees enjoy liberal amounts of paid time off, including 13 days of sick leave per year, 10 paid federal holidays, and 13 to 26 days of paid vacation, depending on years of service.”

- “Retirement Benefits: Federal employees have access to retirement benefits through the Civil Service Retirement System or the Federal Employee Retirement System. Under both plans, retired employees receive an annuity, which is complemented by Social Security benefits and participation in the Thrift Savings Plan that offers 401(k)-type investment options.”

- “Family-Friendly Policies: Another notable benefit of federal employment is family-friendly policies, including flexible work schedules, telecommuting, part-time jobs, and job sharing. Not to mention the fact that federal employees enjoy first priority and subsidies at a number of top-notch day care facilities.”

There is another important benefit of federal employment: extremely high job security. Federal workers are supported by strong civil service protections, and about one-third of them are represented by unions.21 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data show that the rate of “layoffs and discharges” in the federal workforce is just one-quarter of the rate in the private sector.22

Federal workers are almost never fired. An investigation by Government Executive noted, “There is near-universal recognition that agencies have a problem getting rid of subpar employees.”23 Just 0.5 percent of federal civilian workers a year get fired for any reason, including poor performance and misconduct. That rate is just one-sixth of the private-sector firing rate.24 For the senior executive service in the government, the firing rate is just 0.1 percent.25 By contrast, about two percent of corporate CEOs are fired each year, which is a rate 20 times higher than in the senior executive service.26

All in all, the federal government is a very well-compensated place to work. A final piece of evidence can be found by looking at quit rates, or the rates that workers voluntarily leave their jobs. BLS data show that the quit rate in the federal government is just one-quarter the quit rate in the private sector.27 Federal workers know that they have a lucrative combination of compensation and job security, and so they stay much longer than do workers in other industries.

Conclusions

It is sometimes assumed that the federal government should employ the nation’s highest-skilled workers, and that it should pay top dollar to get them. But federal hiring of the very best workers imposes an “opportunity cost” on the economy by drawing talented people away from higher-valued activities in the private sector. Unlike, say, France, where the best university graduates historically have gone into government, the United States has historically prospered because the best and brightest have flocked to places such as Silicon Valley.

Federal pay should be reasonable, and we need competent people in federal jobs, assuming that the jobs are useful ones. But the government should not be one of the highest-paid industries in the nation. Indeed, an advantage of reducing federal pay would be to encourage greater turnover in the static federal workforce. That would help more young people enter government and bring in fresh ideas.

The partial freeze on federal wages under President Obama was a successful effort. Now President Trump and Congress should overhaul the overly generous federal benefits package to reduce costs. It should, for example, end defined-benefit pension plans, as most private-sector employers have done.

Another way to reform federal pay would be to privatize federal jobs where possible. Is the compensation for postal workers, air traffic controllers, and Amtrak employees too high or too low? We can find out by privatizing those activities—as other nations have done—and allowing compensation to be set in the marketplace.

To deal with today’s large budget deficits, policymakers should cut program spending in every federal department. They should also reform federal pay packages and better align wages and benefits to private sector standards.

1 Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2020, Analytical Perspectives (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2019). Excludes the U.S. Postal Service.

2 Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2020, Analytical Perspectives (Washington: Government Printing Office, 2019). Excludes the U.S. Postal Service.

3 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Tables 6.2D and 6.5D, www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm. Data are for civilian federal workers, excluding postal workers.

4 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Tables 6.2D and 6.5D, www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm.

5 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 6.6D, www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm.

6 Chris Edwards, “Federal Pay Tops Most Industries,” Cato at Liberty, Cato Institute, September 21, 2017. The BEA presents data for 19 major private industries, as well as state and local government. I’ve split the federal government between civilian, military, and government enterprises.

7 See Eric Katz, “Federal Employee Union Vows to ‘Open a Can of Whoop Ass’ on Unfriendly Lawmakers,” Government Executive, February 9, 2015.

8 Author’s calculations based on U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Tables 6.2D and 6.5D, www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm.

9 Eric Katz, “Feds Earn 35 Percent Less Than Private Sector Workers, Group Says, “Govexec.com, November 5, 2015. Federal Salary Council reports are available on the Office of Personnel Management’s website at www.opm.gov/oca/fsc.

10 Andrew Biggs and Jason Richwine, “Comparing Federal and Private Sector Compensation,” American Enterprise Institute, June 2011. Biggs and Richwine assess the flaws in the Federal Salary Council approach.

11 Congressional Budget Office, “Comparing the Compensation of Federal and Private-Sector Employees: 2011 to 2015,” April 2017. See also Government Accountability Office, “Federal Workers: Results of Studies on Federal Pay Varied Due to Differing Methodologies,” GAO-12-564, June 2012.

12 James Sherk, “Inflated Federal Pay: How Americans Are Overtaxed to Overpay the Civil Service,” Heritage Foundation, July 7, 2010. See also Rachel Greszler and James Sherk, “Why It Is Time to Reform Compensation for Federal Employees,” Heritage Foundation, July 27, 2016.

13 Andrew Biggs and Jason Richwine, “Comparing Federal and Private Sector Compensation,” American Enterprise Institute, June 2011.

16 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Tables 6.2D, 6.3D, and 6.5D, www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm. To get benefits only, subtract wages from total compensation.

17 Congressional Budget Office, “Comparing the Compensation of Federal and Private-Sector Employees: 2011 to 2015,” April 2017.

18 Congressional Budget Office, “Comparing the Compensation of Federal and Private-Sector Employees: 2011 to 2015,” April 2017, p. 3.

21 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members 2014,” news release, January 23, 2015, Table 3, www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.htm.

22 See the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics monthly news release on Job Openings and Labor Turnover at www.bls.gov/jlt.

23 Eric Katz, “Firing Line,” Government Executive, January–February 2015, www.govexec.com/feature/firing-line/.

24 Andy Medici, “Federal Employee Firings Hit Record Low in 2014,” Federal Times, February 24, 2015.

25 Chris Edwards, “Federal Firing Rate by Department,” Cato at Liberty, Cato Institute, June 6, 2014. And see Eric Katz, “Lower-Ranking Feds Are Nine Times More Likely to Be Fired than Senior Execs,” Government Executive, June 3, 2014.

26 Regarding the CEO firing rate, see Lucian Taylor, “Comment” on Steven N. Kaplan, “Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance in the United States,” Cato Papers on Public Policy 2 (2012–13): 159–64.

27 See the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics monthly news release on Job Openings and Labor Turnover at www.bls.gov/jlt.